When the cat’s away will the rats play?

Monday, 16 March 2020Christmas Island is home to a suite of native animals found nowhere else, but also to invasive species including Asian wolf snakes, giant centipedes, feral cats and black rats. These invasive animals have contributed to many extinctions and declines of Christmas Island’s native species. The Australian Government is undertaking a range of conservation initiatives to safeguard the island’s native wildlife, including an island-wide cat eradication program. A Threatened Species Recovery Hub collaboration with Parks Australia is investigating the potential outcomes of the cat control, including whether rats will need concurrent control. Researchers Michaela Plein and Rosalie Willacy from The University of Queensland report.

Cats and rats are recognised as the most damaging invasive predators for island species, and mitigating their impact is a top priority. On other islands, controlling the top invasive predator has sometimes led to increased abundances of smaller invasive species. For example, numbers of rats increased in some parts of Little Barrier Island, New Zealand, after cat eradication, with reduced breeding success for native birds. While there is potential for negative effects from controlling invasive species in this way, outcomes are uncertain and vary between places, habitats and even over time.

Parks Australia, who manage Christmas Island National Park, want to maximise the outcomes of cat control on Christmas Island by anticipating and managing any unintended consequences. Our research is assisting them to predict potential outcomes, particularly the potential for rat (Rattus rattus) numbers to increase following cat eradication, and whether this would impact nesting birds.

Current and potential future rat impacts are uncertain for Christmas Island due to data deficiencies and because birds co-existed with (now extinct) native rodents as well as abundant land crabs – which may make them less vulnerable to rat impacts.

We tackled the problem in two ways: first, PhD candidate Rosie Willacy weathered the tropical storms and magic of Christmas Island to collect evidence in the field; and second, postdoctoral researcher Michaela Plein developed a predictive computer model.

A one- to two-week-old red-tailed tropicbird chick. Parents begin leaving chicks unattended around this age for extended foraging trips at sea. While unattended, chicks are extremely vulnerable to predation. Image: Rosalie Willacy

Fieldwork warrior Rosie

Rosie describes a typical day: “I get up early on Christmas Island – it will get hot after 11 am – so we will need to finish the field work by lunch at the latest, then we’ll be back out in the field in the late afternoon. Today we will check the battery life of motion-sensor cameras that are monitoring the breeding success and causes of nest failure for the ground-nesting seabird the red-tailed tropicbird (Phaethon rubricauda).

We will scramble around the sharp cliffs, where the nests are tucked away under bushes and in holes of the limestone. The nests are so well hidden that sometimes nothing but the loud alarm call of the adult breeding bird will alert you to their presence.”

Previous studies from 2008 to 2010 showed a mortality rate of up to 95% for red-tailed tropicbird chicks, mostly due to cat predation. Cats have been controlled near one of the colonies since 2010, and breeding success seems to have improved. However, there has been little monitoring to see whether cat predation is continuing, or if rat activity around nests has increased recently. To assess the effects of both cat and rat predation on red-tailed tropicbirds and other threatened Christmas Island species, Rosie is examining patterns of rat abundance and activity across the island, and relating this to forest bird abundance and nesting success, and to seabird nesting success.

Whereas the red-tailed tropicbird has been the seabird “exemplar”, Rosie has used the Christmas Island thrush (Turdus poliocephalus erythropleurus) as the “exemplar” for forest birds. Over the past three years, Rosie has completed almost 200 transect surveys to estimate the abundance of the Christmas Island thrush and other forest birds in parts of the islands with differing numbers of rats. She has also monitored about 200 thrush and tropicbird nests with motion sensor cameras to detect predation.

Rosie’s work depends on gathering data on rat abundance across Christmas Island. To achieve this, she needed to outwit the superabundant, curious and hungry land crabs. During the wet season (and especially during crab migration season), red crabs and robber crabs frequently interfered with traps, making rat detection extremely challenging. For this reason, Rosie first needed to evaluate which method (ink-card tracking, camera traps, cage trapping or DNA hair traps) was best for monitoring rat abundance in this unique ecosystem.

Rosie also measured several other ecological factors (like crab density, crazy ant presence, habitat type) that might explain any variation in rat density, and help us understand the relationships between cats, rats, other species on the islands, and whether cat removal is likely to lead to more rats.

Recently hatched Christmas Island thrush chicks. This Endangered subspecies is likely impacted to varying degrees by native land crabs and birds of prey, as well as invasive predators including cats, rats, giant centipedes and crazy ants. On other islands, island thrush subspecies have become extinct due to the impacts of rodents. Image: Rosalie Willacy

Desktop warrior Michaela

Meanwhile, Michaela Plein reports from her desk: “While I sit in front of my desktop staring at my code, my mind wanders back to the meeting with Parks Australia staff the previous day. Did we include all the important species in the interaction network for Christmas Island? Do feral cats and black rats really eat all these animal species? Would predation by red and robber crabs on rats affect the rat population?

And how heavy are feral cats and black rats on Christmas Island? Because that affects how much they need to eat. Finally, my computer spits out yet another result for the eradication scenarios and I wonder how to best show the uncertainty in these estimates.”

Modelling the potential outcomes of invasive species eradications is difficult; often we know little about how the species interact, and the larger a species network the higher the potential for uncertainty.

We have investigated two key questions: 1) Can we predict the effects of eradicating cats only, versus eradicating cats and rats, on other island species?; and 2) What cat and rat densities threaten bird species like the red-tailed tropicbird?

The modelling allows us to estimate the rat numbers that will cause tropicbirds to decline, showing threshold rat density that should not be exceeded if the tropicbird population is to survive over time.

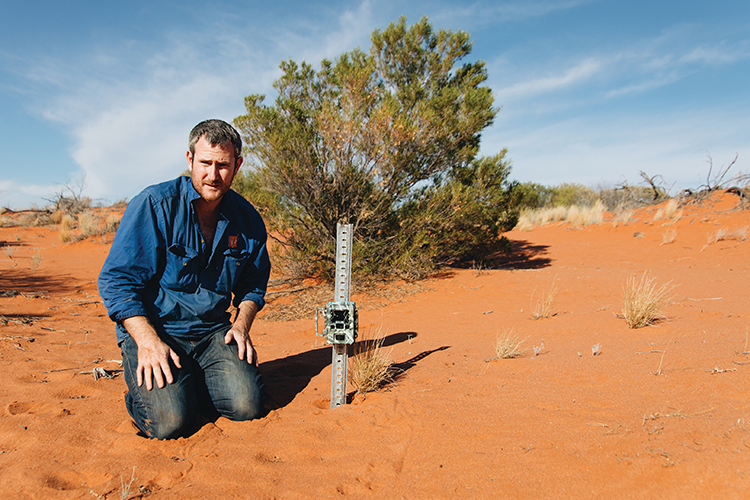

Rosie services a motion sensor camera installed at a brown booby nest. A number of brown boobies were monitored alongside red-tailed tropicbirds to compare breeding behaviour-related differences in predation impacts. Image: Scott Macor

Two tactics come together

While Michaela’s modelling allows us to broadly explore the influence of cats and rats on key species, Rosie’s field work is providing baseline data on the rat populations of Christmas Island and the impacts of rats on forest and seabirds, as well as developing methods for ongoing monitoring of rats during and after cat eradication.

The hope is that these combined efforts, in the field and on the screen, can help inform future rat management on Christmas Island to aid in the protection of the island’s unique animals. Because of the similar stories of invasive species and biodiversity loss on other islands, we also hope that the monitoring and modelling approaches developed and information gained can be used to inform other cat eradication projects on islands across the globe.

This Threatened Species Recovery Hub project is being carried out in a collaboration between The University of Queensland, Parks Australia and Christmas Island National Park.

Rosalie Willacy’s fieldwork was made possible by generous in-kind support from Parks Australia as well as funding from the Australia and Pacific Science Foundation, Birdlife Australia (Stuart Leslie Bird Research Award), Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, the Ecological Society of Australia (Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment) and the Royal Society of Zoology, NSW (Ethel Mary Read Research Grant).

Christmas Island. Image: Chris Bray Photography

For further information

Eve McDonald-Madden - e.mcdonaldmadden@uq.edu.au

Sarah Legge - sarahmarialegge@gmail.com

Rosalie Willacy - r.willacy@uq.edu.au

Michaela Plein - michaela.plein@gmx.de

Top image: A juvenile rat braves the jungle floor during the day on Christmas Island – the domain of red and robber crabs, which are likely predators and competitors of rats. Image: Rosalie Willacy

-

Combating a conservation catastrophe: Understanding and managing cat impacts on wildlife

Tuesday, 06 October 2020 -

Cat-borne diseases and their impacts on human health

Monday, 19 October 2020 -

Cat-borne diseases and their impacts on agriculture and livestock in Australia

Monday, 07 December 2020 -

li-Anthawirriyarra Sea Rangers managing cats on West Island

Thursday, 16 September 2021 -

The impact of roaming pet cats on Australian wildlife

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Caring for Country: Managing cats

Tuesday, 09 November 2021

-

Small mammal declines in the Top End - Causes and solutions

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Fire, cats, foxes and land management: Lessons learned

Wednesday, 02 September 2020 -

How the brown-skua, a top-native predator, is responding to rabbit eradication on Macquarie Island

Friday, 09 July 2021 -

Addressing our wildlife cat-astrophe

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Cat eradication to help threatened species on Christmas Island

Tuesday, 05 September 2017 -

Cats are killing millions of Australia’s birds

Sunday, 22 October 2017 -

Feral cats: An Australian Government perspective

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

FoxNet: A game changer for fox control

Tuesday, 30 June 2020 -

Success, failure and lessons learned on Australian islands

Wednesday, 04 May 2016 -

Testing cat baiting on Kangaroo Island

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The conundrum of cats in Australia

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The fire, the fox and the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

The mathematics of cats

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The unnoticed toll of cats on reptiles

Monday, 25 June 2018 -

Tiwi Island mammals: Saving the brush-tailed rabbit-rat

Tuesday, 11 September 2018 -

Tracking cats to help the night parrot

Wednesday, 05 June 2019 -

Watching Macquarie Island transform after a massive intervention

Friday, 20 October 2017 -

When rabbits are off the menu, what’s for dinner?

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Threatened Species Recovery Hub to join fight against feral cats

Tuesday, 03 November 2015 -

TSR contributes to Feral Cat Taskforce

Monday, 28 March 2016 -

One cat, one year, 110 native animals: Lock up your pet, it’s a killing machine

Wednesday, 28 October 2020 -

Cat science finalist for Eureka Prize

Monday, 28 September 2020 -

Cats have $12 million impact on agriculture in Australia

Monday, 07 December 2020 -

Cat diseases have $6 billion impact on human health in Australia

Thursday, 15 October 2020