Fire, cats, foxes and land management: Lessons learned

Wednesday, 02 September 2020Fire is a feature of just about every habitat across Australia, but it operates in myriad ways within landscapes – from frequent low-intensity fires in tropical savannas to once-in-50-years crowning fires in Victorian eucalypt woodlands. There are broad trends and theories that hold in fire ecology in Australia, yet when it comes to understanding fire for conservation management, local management is absolutely essential. Dr Hugh McGregor of the University of Tasmania/Arid Recovery explains why.

I learnt the lesson of the importance of local land management some years ago when I was researching feral cats in the Kimberley. After I collected all the GPS movement data from my collared cats and had done all the fire-scar mapping, I plugged in my data for a statistical answer as to how cats interact with fires in the landscape. At first, the results were resoundingly disappointing. Essentially, the stats came back that fires and movements by cats were not significantly related. It meant I would have had a boring study to write about. I know you have to be impartial with science, but of course I was quite annoyed at this. It contradicted many of my observations. I had recorded many examples of cats travelling to fire scars from far away, and had strong evidence that cats were more efficient hunters in fire scars than in unburnt habitats. So why was the first analysis I ran telling me that the cats didn’t change their movement behaviour in response to fires?

A feral cat with a native plains mouse. The GPS-collared feral cat was being tracked by Dr McGregor as part of a hub research collaboration between Arid Recovery and the University of Tasmania. Image: Hugh McGregor

Managing land for wildlife

It turns out I was missing the most critical variable of all: management. Many of the feral cats I studied were captured and collared around the most intensively managed portions of Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s (AWC) Mornington Wildlife Sanctuary. This area was completely destocked of cattle, and native vegetation had recovered. In addition, the occurrence of intense wildfires had decreased as a result of strategic prescribed burning after every wet season and fire suppression in the mid-to-late dry season. The result was an increase in the extent of unburnt, complex vegetation, and native small mammals had consequently greatly increased in numbers. However, this increase in mammal populations also meant that when habitats did burn, a higher density of native animals become exposed by the removal of cover, and cats were motivated to hunt there.

The opposite was true of areas where fire and stock had not been managed so intensely. I also collared feral cats in nearby areas that were not destocked and where fire management had been less intensive or effective. In these areas, native wildlife were scarce even before a fire went through. As a result, fires did not expose so many prey, simply because they were few and far between in the first place. Fire scars in such locations were not lucrative hunting spots, and cats in these areas would actively avoid those places.

The reason my original analysis did not report any relationship between fires and cat movement was that the two processes cancelled each other out. Half my cats were in the intensively managed areas, half in areas with minimal management, and they averaged out to show no pattern between fires and movement by cats. When I ran a new analysis, this time incorporating management regime, the results emerged: extreme selection by cats of fire scars where management was intensive and native mammal density was high, and avoidance by cats of fire scars in areas with less intensive management and low small mammal density. It was a crystal clear lesson of the benefits of embedding conservation research within well-understood local land management programs.

A University of Melbourne study in Victoria’s Otway Ranges led by Dr Bronwyn Hradsky observed

a dramatic increase in feral predators after a prescribed burn. Image Bronwyn Hradsky

Same patterns north and south

Several Threatened Species Recovery Hub research projects across Australia have extended this line of research into the interactions between introduced predators and other threats. This work has been conducted in close partnership with managers, further confirming the value of an applied conservation research approach.

In Northern Australia, the Northern Territory Government and Charles Darwin University have found that areas across the Top End with more frequent fire and higher levels of feral herbivores have increased feral cat occurrence. Likewise, on the Tiwi Islands, research by Hugh Davies and the Tiwi Land Rangers has shown a similar pattern: more frequent severe fires equal more cats. And the opposite was true, too. Where fire management had been most successful, structural complexity of the vegetation was key to obtaining lower detection rates for cats. Parts of the landscape that retain such complex vegetation are critical to the persistence of Endangered mammals like the brush-tailed rabbit-rat.

In southern Australia, detailed research conducted in the Otway Ranges of south-west Victoria has revealed similar patterns, this time with foxes. In this landscape, fires are far less frequent, but individual fires can be of higher severity, removing almost all cover over substantial areas. And fox scats from burnt areas contain more medium-sized native mammals than scats from unburnt areas. As part of a Threatened Species Recovery Hub project, researchers and managers are working together to maximise opportunities to learn from and optimise management. To achieve this, the management is structured as field research and includes nearby areas with no control and patchworks of control burns. And just as for the work in the Kimberley, they are able to investigate the interaction between predators, fire and threatened animals due to the fact it is well-managed landscape that still retains its threatened animals.

These research projects, carried out in very different habitats and with both cats and foxes, all point to the risk of amplified predation after fire. Following the 2019–20 bushfires, increased predation risk could cause as much or more population loss, for some species, than the fire event itself. Reducing post-fire predation by cats, foxes and wild dogs is now one of the priorities for conservation managers across the country. Local knowledge about the locations of susceptible native species, and observations of changes in the density and behaviour of cats and foxes, will be essential for targeting these interventions most effectively.

Working directly with managers makes research more focused, useful and fun, the best combination of attributes you could hope for in field research.

An early dry season controlled burn at Glenroy Station in the Kimberley. Patchy low-intensity early burning is a common strategy aimed at avoiding large, intense, late dry season fires. Image: Hugh McGregor

Further information

Hugh McGregor - hugh.mcgregor@utas.edu.au

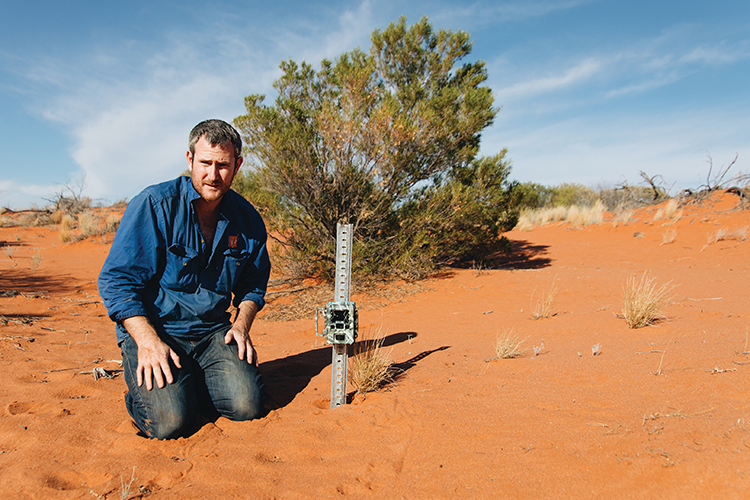

Top image: Dr Hugh McGregor radio-tracking a feral cat at Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Mornington Station, Kimberley, Western Australia. Image: Hugh McGregor

-

Small mammal declines in the Top End - Causes and solutions

Monday, 31 August 2020 -

Cats are killing millions of Australia’s birds

Sunday, 22 October 2017 -

Fire leads to spike in invasive predators

Tuesday, 23 May 2017 -

FoxNet: A game changer for fox control

Tuesday, 30 June 2020 -

Testing cat baiting on Kangaroo Island

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

The fire, the fox and the feral cat

Tuesday, 06 June 2017 -

Tiwi Island mammals: Saving the brush-tailed rabbit-rat

Tuesday, 11 September 2018 -

When rabbits are off the menu, what’s for dinner?

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

When the cat’s away will the rats play?

Monday, 16 March 2020 -

Threatened Species Recovery Hub to join fight against feral cats

Tuesday, 03 November 2015 -

TSR contributes to Feral Cat Taskforce

Monday, 28 March 2016 -

Cat science finalist for Eureka Prize

Monday, 28 September 2020