Researcher Profile: Hayley Geyle

Wednesday, 28 October 2020Hayley Geyle is a Research Assistant at Charles Darwin University who has been instrumental in Threatened Species Recovery Hub research to identify the Australian species at greatest risk of extinction.

I spent much of my childhood in nature – family camping trips were always our go-to holiday. I have fond memories of feeding the kookaburras with my dad at Roses Gap, and exploring the Grampians with my cousins. Naturally this led to a close affinity with nature and wildlife, but it wasn’t until my later years at high school that I decided I wanted to pursue a career in conservation.

When I started my VCE, I signed up for environmental science. It was the first year the unit had run at my school, after an enthusiastic teacher managed to scrape a measly 12 students together. We figured it’d involve lots of fieldtrips – and we weren’t disappointed. I was inspired by my teacher’s passion for the natural world. He was an exceptional educator, who opened my eyes up to many conservation issues. But, ultimately, it was a school trip to Mount Rothwell, and my first interaction with an eastern quoll and an eastern barred bandicoot that sealed my fate. I was shocked to learn that both of these incredible species now depended on a predator-proof fence for their survival, and I knew then that I wanted to work with wildlife.

Checking the pouch of a northern brown bandicoot. Image: Cassandra Holt

Checking the pouch of a northern brown bandicoot. Image: Cassandra Holt

Fate sealed

I went on to study environmental science at Deakin University, a course I can’t recommend highly enough. All of my lecturers were fantastic, and the course offered some great hands-on experiences, including a study tour to Borneo. I signed up to do an honours project on small mammals in Wilson’s Promontory National Park before an opportunity surfaced to work on the brush-tailed rabbit-rat on the Tiwi Islands. After finishing my honours degree, and realising just how much I loved working in the tropics, I made the move to Darwin. I had no job lined up, but kept afloat doing some casual research work on introduced predators with Deakin University and Parks Victoria. I was optimistic that something might pop up in Darwin.

My timing couldn’t have been better. I was absolutely delighted to secure a part-time zookeeper position at the Territory Wildlife Park looking after northern quolls. Around the same time, I was lucky enough to be offered a casual research position at Charles Darwin University (with much help from one of my former honours supervisors, Brett Murphy), working with the Threatened Species Recovery Hub. These two roles happily complemented each other for the next year or so, but as much as I loved spending time with my spotty family, I soon realised that zookeeping wasn’t for me.

Research beckons

When a full-time position became available with the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, I jumped at the opportunity. Research is my true passion, and I was particularly keen on working on projects that would contribute directly to the conservation of threatened species. For the past three years, I’ve been working on two main projects, identifying the animal species on the brink of extinction and investigating the impacts of introduced predators on native species (while also chasing northern brush-tailed phascogales in my spare time).

So far, we have completed assessments of extinction risk for birds, mammals, freshwater fish and reptiles, which wouldn’t have been possible without the input of many amazing ecologists from across the country. Our ultimate goal is to raise awareness of the species at greatest risk of extinction, and to generate more support for their conservation. There are some signs to suggest that it’s working. Following the publication of our paper on imperilled birds in 2018, resources were invested into new survey and management effort for the two species identified to be at greatest risk – the King Island brown thornbill and the King Island scrubtit – that resulted in the discovery of new populations. We’re hopeful that this work will also lead to positive outcomes for our less furry and feathery critters.

Further information

Hayley Geyle - hayley.geyle@cdu.edu.au

Top image: Setting up a remote-sensor camera to target northern brush-tailed phascogales on Melville Island. Image: Cassandra Holt

-

The Australian freshwater fishes at greatest risk of extinction

Tuesday, 01 September 2020 -

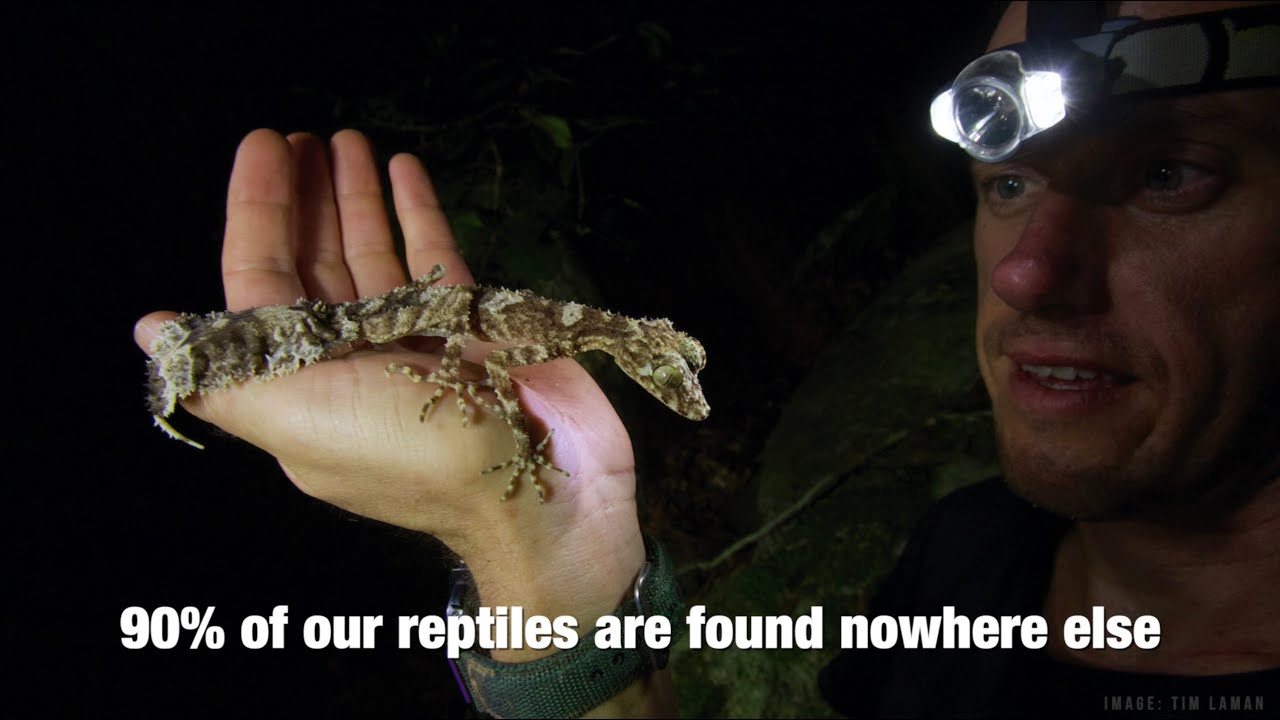

Preventing extinctions of Australian lizards and snakes

Tuesday, 02 February 2021 -

Saving Tasmania's difficult birds

Monday, 27 July 2020 -

Please save these frogs: The 26 Australian species at greatest risk of extinction

Friday, 20 August 2021

-

Big trouble for little fish: The 22 freshwater fishes at risk of extinction

Wednesday, 21 October 2020 -

Unique yet neglected: The Australian snakes and lizards on a path to extinction

Tuesday, 10 November 2020 -

A review of listed extinctions in Australia

Tuesday, 12 November 2019 -

No surprises, no regrets: Identifying Australia's most imperilled animal species

Monday, 24 September 2018 -

Tasmanian birds top endangered species list

Thursday, 07 July 2016 -

2020 target set for more threatened species

Monday, 28 March 2016 -

Keeping up with biodiversity loss

Thursday, 26 November 2015 -

Reflections on loss

Thursday, 09 June 2016 -

Aussie icons at risk: Scientists name 20 snakes and lizards on path to extinction

Tuesday, 29 September 2020 -

22 Australian freshwater fish at risk of extinction

Tuesday, 29 September 2020 -

‘Australian Fritillary’ and ‘Pale Imperial Hairstreak’ top list of butterflies at risk of extinction

Tuesday, 27 April 2021 -

These frogs need our help: Scientists name the Australian frogs at greatest risk of extinction, four likely already lost

Friday, 20 August 2021