Learning from a failed biodiversity offset

Wednesday, 24 May 2017The widening and realignment of the Hume Highway over 140 km between Coolac and Holbrook in NSW required the removal of thousands of native trees. Governments in Australia and internationally are increasingly turning to biodiversity offsets as a way to compensate for the environmental harm of projects which otherwise deliver important social and economic outcomes.

Many native animal species rely on tree hollows for breeding and den sites. The Hume Highway construction area was known to contain threatened animal species that are reliant on tree hollows for nesting including the EPBC listed superb parrot, and NSW listed squirrel gliders and brown treecreepers. To compensate for the loss of tree hollows, the developer was required to install one nest box in nearby woodland as an offset for every lost tree hollow, and to design specific nest boxes to suit each of the target threatened species. In total 587 nest boxes were installed, and the program cost NSW Roads and Maritime Services (RMS) $213,000.

Researchers conducted 3,000 checks of the nest boxes along the Hume Highway in southern NSW. Image: Daniel Florance

Researchers conducted 3,000 checks of the nest boxes along the Hume Highway in southern NSW. Image: Daniel Florance

While the theory of biodiversity offsets is sound, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of many offset techniques. RMS engaged The Australian National University to monitor the outcomes of the Hume Highway project. The results have now been analysed and published in Biological Conservation.

Almost three thousand nest box checks over four years found that no Superb Parrots used the nest boxes and there were only nine recordings of treecreepers and squirrel gliders– and none in a box that was specifically designed for them. Clearly this offset failed to provide habitat for the target threatened species, but what else have we learned?

Squirrel Gliders depend on tree hollows for dens and breeding. Image: ANU

Squirrel Gliders depend on tree hollows for dens and breeding. Image: ANU

The nest boxes were used roughly half of the time by common native species including brush-tailed possums and yellow-footed antechinus, and introduced black rats and feral bees: so nest boxes can provide an ecological role for common species. It is possible that nest boxes could provide habitat for even the threatened species in this study, but further investigation, trials and testing would be needed before we can have confidence in this.

Yellow footed antechinus were one of the common species using the nest boxes. Image: Mason Crane

Yellow footed antechinus were one of the common species using the nest boxes. Image: Mason Crane

Eight percent of the nest boxes fell out of trees or were stolen in the four year monitoring period. Given that trees are usually 80 to 120 years old before they form tree hollows, it is fair to assume that most nest boxes would therefore fail before they could provide suitable habitat: so any program relying on nest boxes must assume a long-term commitment to monitoring and maintenance, and budget accordingly.

And finally the conditions of this offset only required the proponent to erect the nest boxes, even if they then failed to provide habitat for threatened species. For the public to have confidence that offsets are fair compensation for environmental harm, future offset conditions could specify minimum outcomes or performance standards and require reporting to the public of offset compliance and effectiveness. In that way, developers would be responsible for ensuring that offsets achieve their intended outcomes, and it may discourage developers from using unproven techniques.

You can read more about the assessment of the Hume Highway nest box offset in this story by the ABC.

Top image: Superb Parrot emerging from tree hollow. Photo: Dave Curtis

Top image: Superb Parrot emerging from tree hollow. Photo: Dave Curtis

Related Videos

-

Target based ecological compensation: an approach that aligns compensation with conservation targets

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

Introduction to biodiversity offsetting - the basics of what biodiversity offsetting involves

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

Why do we offset? – under what circumstances might be consider a biodiversity offset

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

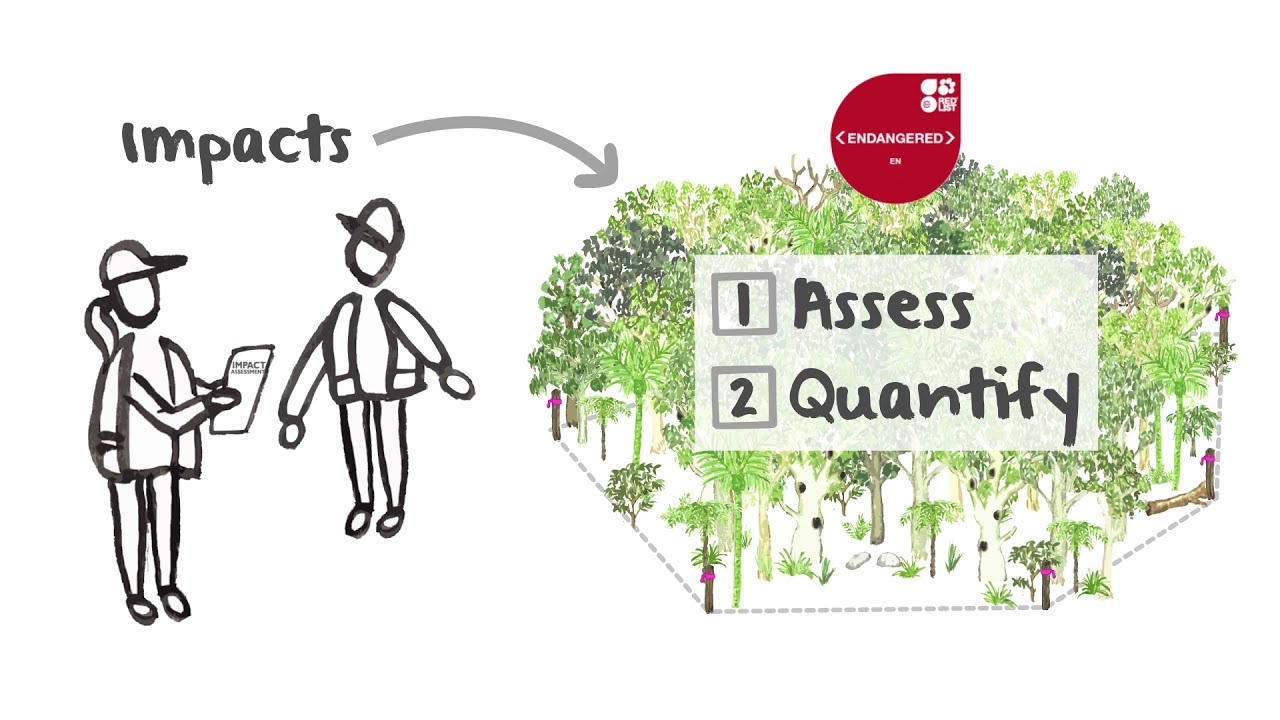

What do we offset? – how do we describe and measure biodiversity for the purposes of offsetting

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

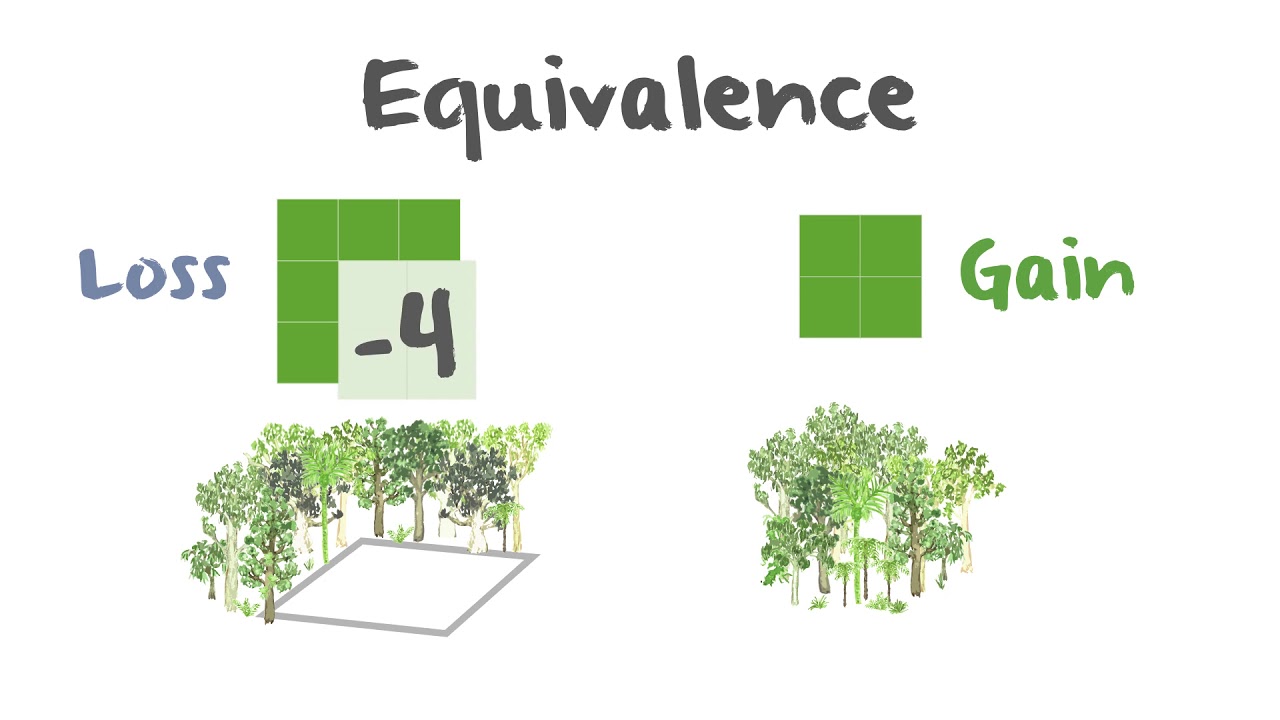

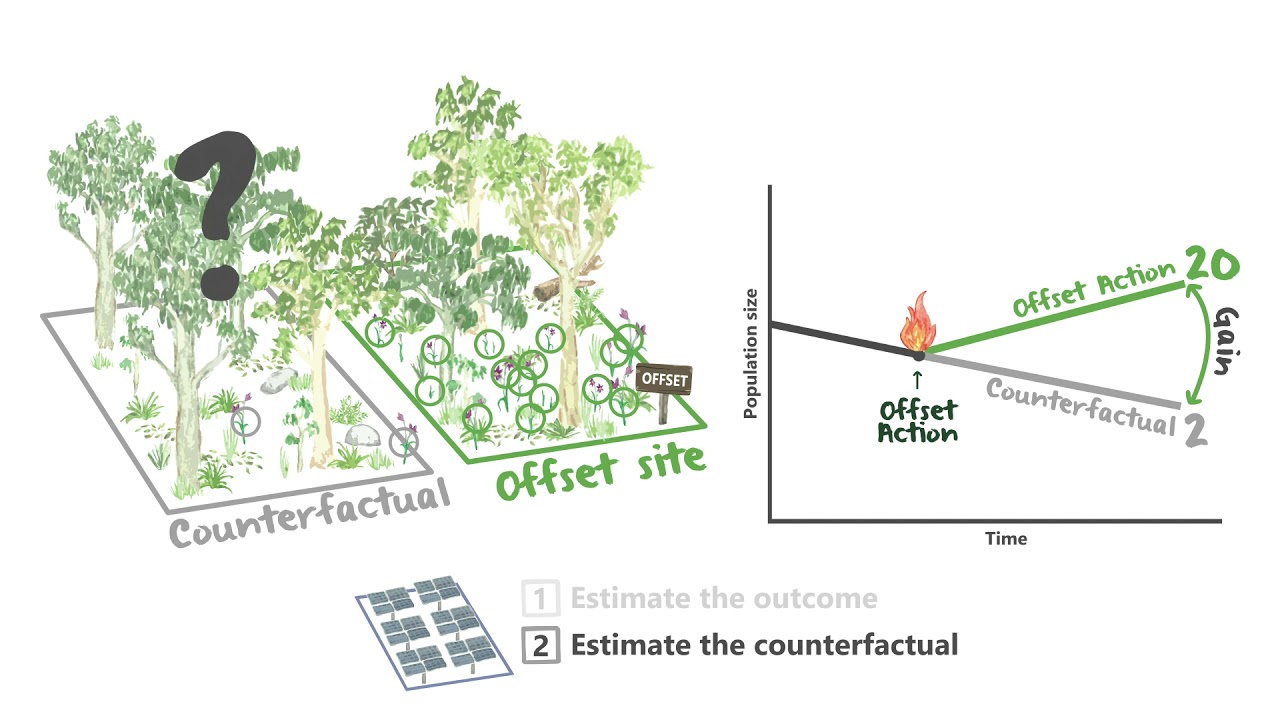

Calculating losses and gains – how to estimate the amount of gain from an offset

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

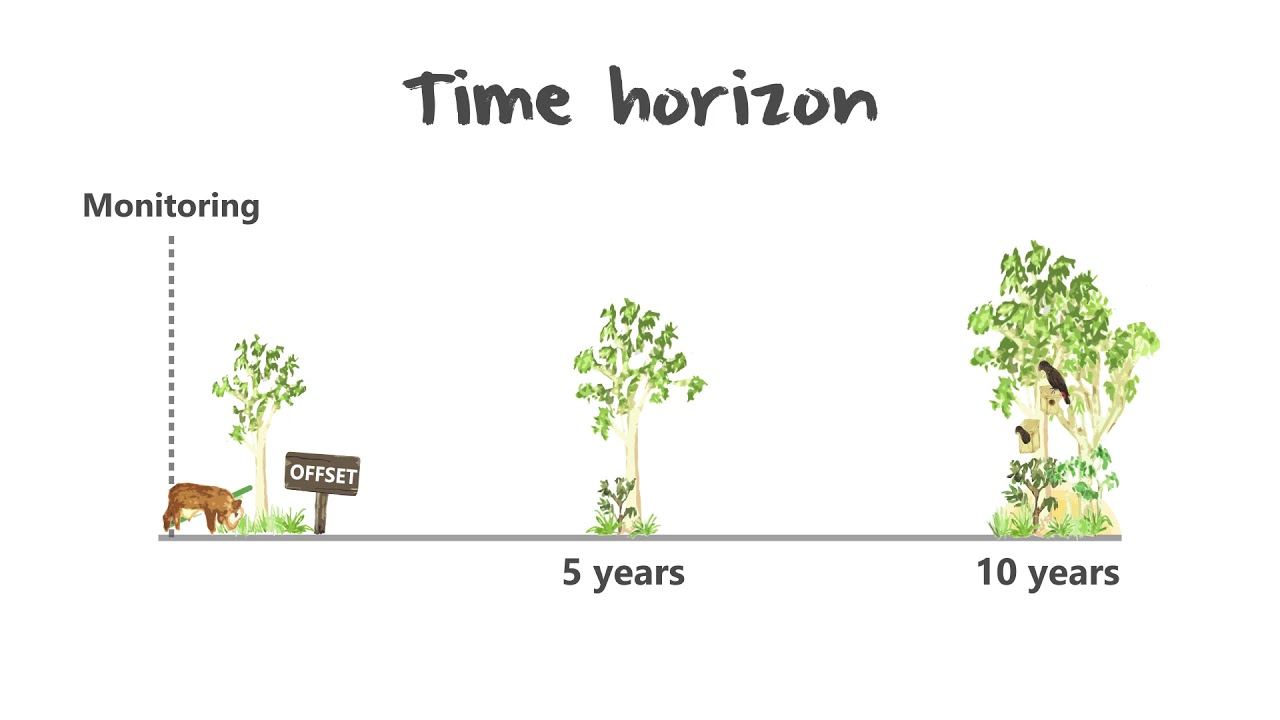

Uncertainty, time lags and multipliers – adjusting estimates of gain from an offset

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

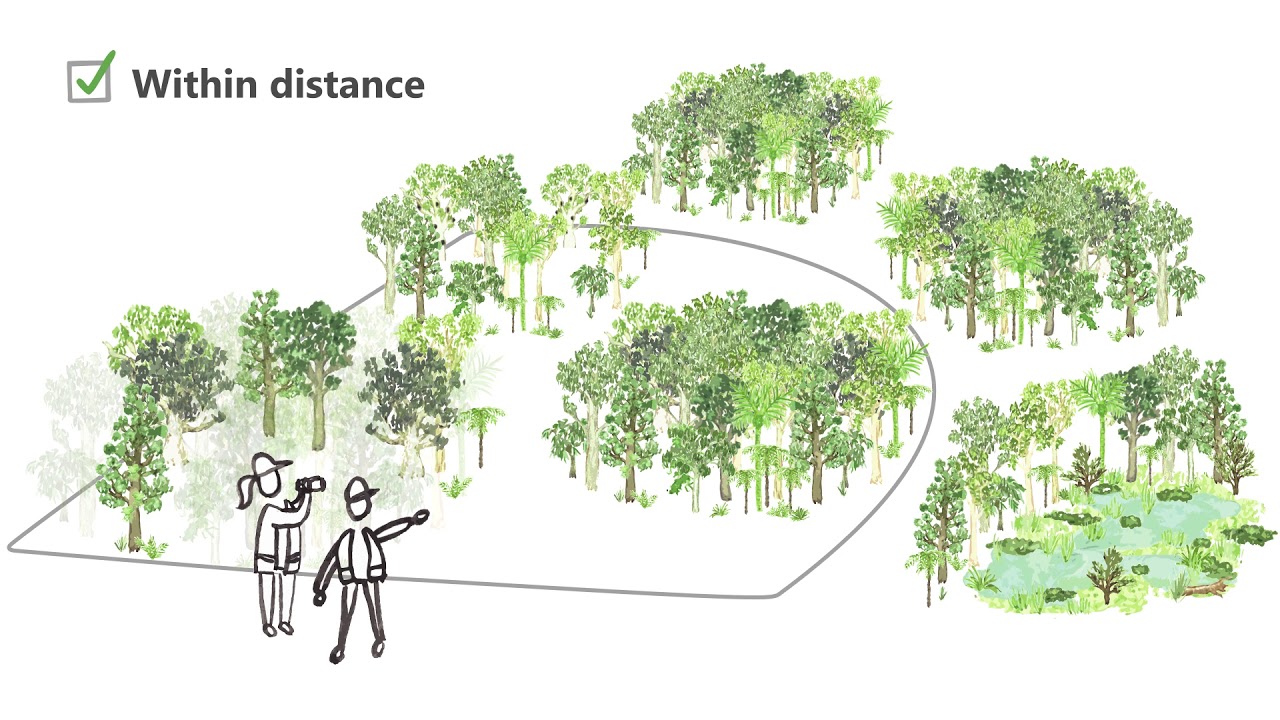

Offset rules – setting constraints and requirements to help make offsets more effective

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

Spatially strategic offsets – coordinating offset actions for greater benefits

Wednesday, 02 June 2021 -

Monitoring & evaluation – tracking the performance of individual offsets and offset programs

Wednesday, 02 June 2021