The experiences of early career scientists in the hub

Wednesday, 08 December 2021Well over 100 early career researchers across the country worked on Threatened Species Recovery Hub research projects, including 77 post-doctoral researchers and 40 research assistants. These dedicated people made an incredible contribution to the achievements of the hub and the hub also aimed to provide a highly supportive environment and developmental opportunities. Many of these people have gone on from the hub to far more senior roles where they will continue to make a major contribution to threatened species research and conservation across Australia.

We asked a few of our early career scientists about their experience being part of the hub. Here is what they had to say.

|

|

Hamsini Bijlani (Ecologist, Environs Kimberley) I’ve been supporting the Ngurrara and Karajarri Rangers to undertake a project which has been exploring interactions between fire and biodiversity on their desert Countries. As an ecologist, I provided training and technical scientific support to the rangers where needed, for things like designing, planning and carrying out surveys, ecological trapping methods, species identification and data management. |

Ngurrara Ranger Emily checking pitfall traps during a survey. Image: Hannah Cliff

Ngurrara Ranger Emily checking pitfall traps during a survey. Image: Hannah Cliff

It is an exciting project to be working on for a number of reasons. The Great Sandy Desert is very poorly studied in terms of Western science, so we are filling massive ‘Western science’ knowledge gaps. We are using a two-way learning approach and also documenting cultural knowledge about desert biodiversity and fire at a crucial time when groups like Ngurrara still have pre-contact elders. Lastly, the findings will be used to directly inform management decisions by these groups, who are important land managers, and part of one of the largest and most important conservation workforces in Australia.

Hamsini, Alfie and Elton discuss the tallies of different species during a survey on Ngurrara Country. Image: Malcolm Lindsay

Hamsini, Alfie and Elton discuss the tallies of different species during a survey on Ngurrara Country. Image: Malcolm Lindsay

There is interest in this project among other groups, so although we have come to the end of the Threatened Species Recovery Hub I hope that we can find a way for the project to continue and expand.

I have learnt so much and enhanced my skills as an ecologist, shared amazing experiences with the rangers, formed important relationships, and learnt a lot about the cultural aspects of fire and biodiversity from rangers and elders. I have also fallen in love with the desert’s very remote and beautiful landscapes.

Alfie and Hamsini measure a legless lizard trapped during a survey on Ngurrara Country. Image: Valerie Dunsmore

Alfie and Hamsini measure a legless lizard trapped during a survey on Ngurrara Country. Image: Valerie Dunsmore

|

|

Dr Elisa Bayraktarov (Research Fellow, The University of Queensland) As part of the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, I worked closely with talented and visionary scientists at The University of Queensland and The University of Sydney, as well as with an extended team of 49 project partners, to create the world’s first Threatened Species Index (TSX). |

The index tracks and reports on Australia’s threatened species in the same way that the ASX tracks changes in the health of our economy. There is no doubt that the TSX will be Australia’s No 1 reporting tool for telling us how our threatened species are faring.

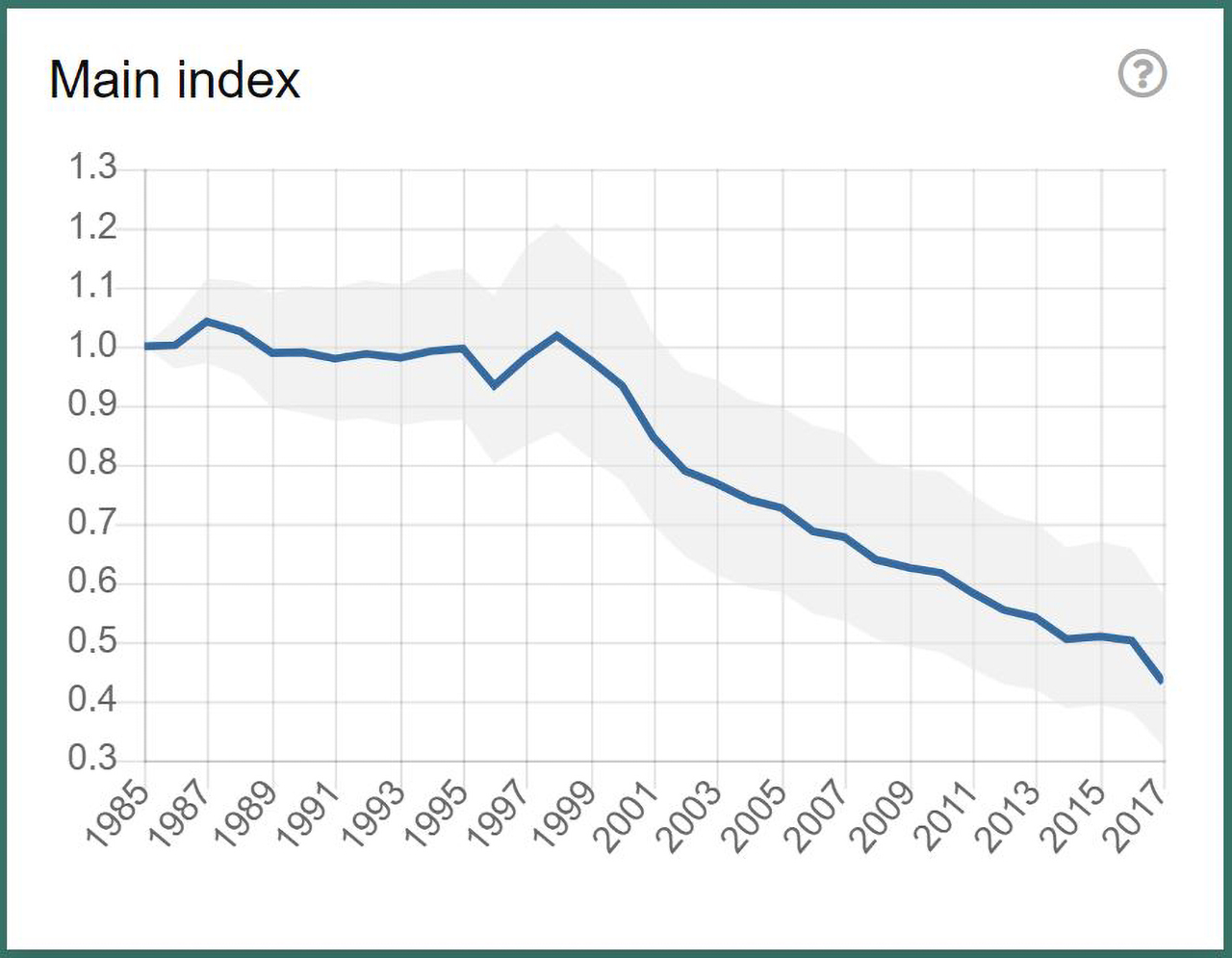

The trend for population sizes of threatened birds, plants and mammals between 1985 and 2017 based on all available monitoring data. Credit: TSX.org.au

The trend for population sizes of threatened birds, plants and mammals between 1985 and 2017 based on all available monitoring data. Credit: TSX.org.au

Among the things that I enjoyed most about being part of the hub were the close collaboration with data custodians, including BirdLife Australia and many other government agencies and non-government groups. In total, we worked with over 300 data custodians. This close collaboration was essential for the success of the project and its continuation beyond the hub’s lifetime. The partnership with the web app developer Planticle was also essential to building the workflow that turns vast amounts of monitoring data from 406,000 surveys over more than 50 years at 20,000 locations across Australia into synthesised and explorable trends. The TSX has become the largest threatened species data collection made from standardised monitoring.

Gouldian finches are one of 67 bird species with data in the index. Image: Glenn Ehmke

Gouldian finches are one of 67 bird species with data in the index. Image: Glenn Ehmke

My hub role gave me the experience, networks and relationships to establish a national reputation for expertise in developing biodiversity indicators, models and web visualisation tools. During my time at the hub, I also learned a great deal about effective communication of research findings to decision-makers and the public. I am now employed at Griffith University as the manager of the national digital innovation program, EcoCommons Australia, where I lead a team of software engineers (DevOps), scientists, science communicators, trainers and analysts to build the platform of choice for ecological and environmental modelling.

|

|

Dr Payal Bal (Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne) I grew up in a city in India with sparkling views of the Himalayas. This inspired awe for nature from a very early age. Since my early investigations of insects in our garden, and the curiosity about the diversity of life instilled in me by my dad’s collection of National Geographic magazines, I have meandered through India, Scotland and Australia studying or working in conservation. |

Now, I am an early career researcher with the Quantitative and Applied Ecology group, where I develop integrated ecological–economic models for large-scale biodiversity assessments.

As part of the NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub, I worked as a spatial analyst evaluating the impact of the 2019–20 wildfires on Australian invertebrates. This work revealed the plight of Australian invertebrates following the wildfires: habitat loss for at least 14,000 species of invertebrates; at least one species considered likely extinct (Banksia montana mealybug in Western Australia); and a doubling of the number of species recommendations for Australia’s list of nationally threatened invertebrates.

The Kangaroo Island marauding katydid is only known from Kangaroo Island and large portions of its known range were impacted by fire. Image: Richard Glatz

The Kangaroo Island marauding katydid is only known from Kangaroo Island and large portions of its known range were impacted by fire. Image: Richard Glatz

While the insights gained were disheartening, to say the least, I thoroughly enjoyed working on this project thanks to an incredibly knowledgeable project team who made for a stimulating, inclusive and encouraging research environment. I enjoyed the problem-solving aspects of the work (i.e., dealing with large and messy species datasets, and finding efficient ways of running spatial analyses for many thousands of species) and gained motivation from the fact that the insights from our analyses had immediate relevance for national and regional conservation decision-making. The work has drawn new collaborations, helping me to expand my network and give me new ideas to chart my course in conservation science.

|

|

Dr Leigh-Ann Woolley (Research Associate, Charles Darwin University) I’m a wildlife ecologist and discovered my love for nature while growing up in the African bush. From the African elephant to the smallest native rodents in northern Australia, I have dedicated my life to solving conservation problems to help protect these animals and the complex landscapes they live in. |

As a Research Associate at Charles Darwin University, I was part of a Threatened Species Recovery Hub project looking at the impact of feral, stray and pet cats across Australia. In particular, I modelled large datasets of cat diet studies to quantify the impact of cats on birds, mammals, reptiles, frogs and invertebrates and to find out whether common characteristics determined the likelihood of an animal being killed by cats.

Leigh-Ann bagging a northern brushtail possum during a trapping exercise with Charles Darwin University. Image: Teigan Cremona

Leigh-Ann bagging a northern brushtail possum during a trapping exercise with Charles Darwin University. Image: Teigan Cremona

Being part of the hub gave me mentorship from some of the best conservation scientists in Australia, vital network connections throughout the country, and absolutely invaluable experience to progress my career. I’m now based in the spectacular Kimberley and managing WWF’s Western Australian species team, where we’re partnering with Indigenous rangers to find innovative solutions to the threats faced by the unique wildlife of this special wilderness region. Unless we change the way we care for our environment and look for sustainable solutions by integrating both Traditional and Western science, we’ll continue to lose a lot more of our world’s extraordinary biodiversity.

| Top image: Dr Leigh-Ann Woolley bagging a northern brushtail possum during a trapping exercise with Charles Darwin University. Image: Teigan Cremona |

| Dr Leigh-Ann Woolley Profile photo. Image: Ryan Taylor |

| Dr Payal Bal Photofile photo. Image: Payal Bal |

| Hamsini Bijlani profile photo. Image: Damian Kelly |

| Elisa Bayraktarov profile photo. Image: German Scholars Organisation |