This ongoing species loss is accompanied by an equally alarming rate of increase in the number of species listed as threatened, and in population declines of listed species. While almost no species have been down- listed due to recovery, a startling 46 species have been up-listed since the establishment of the

(the EPBC Act) due to ongoing or accelerated declines.

So, what is working? For a small minority of species, intensive management (such as exclosure fencing, island eradications of invasive species and translocations to cat-free islands) is producing some recovery.

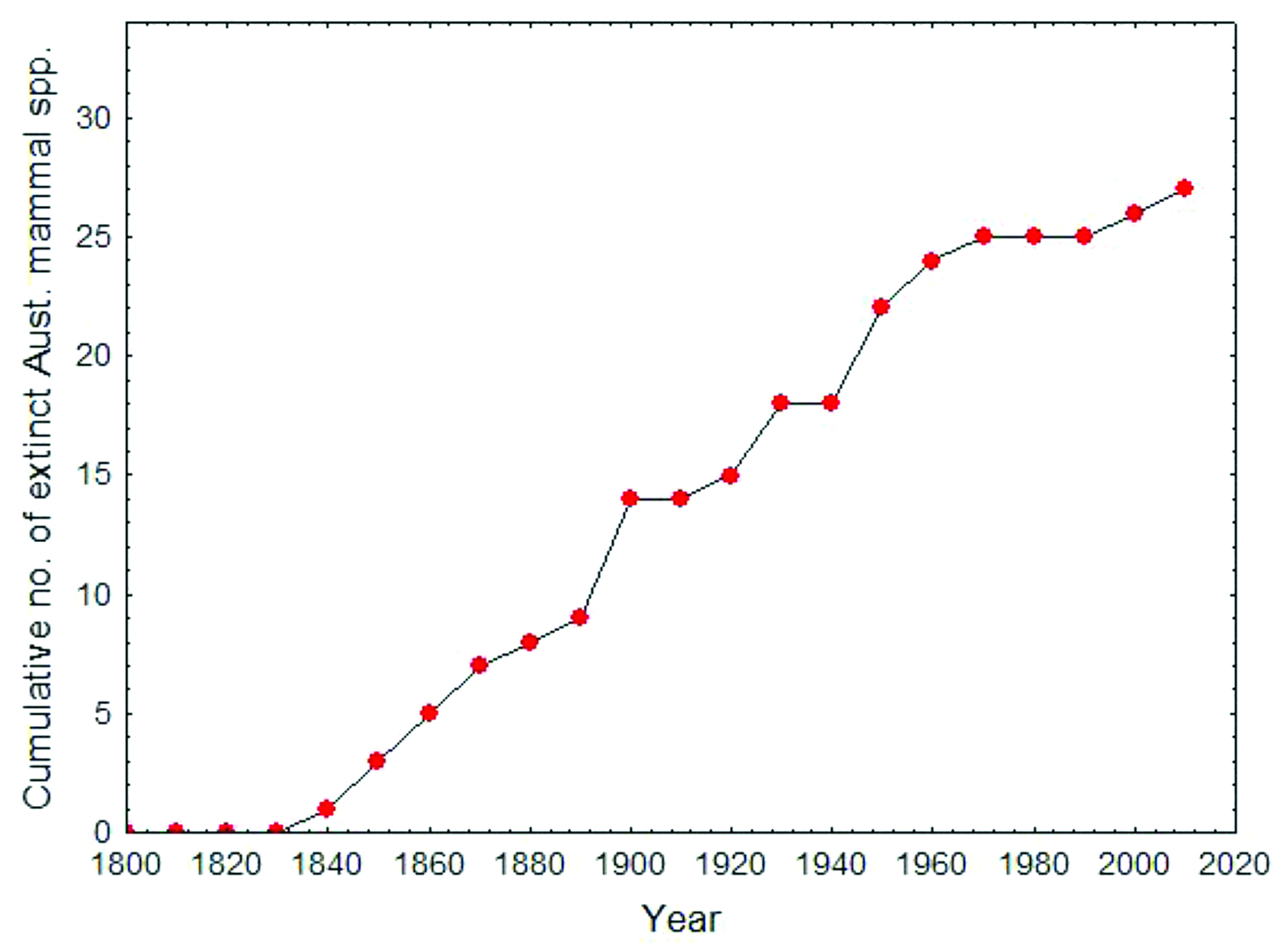

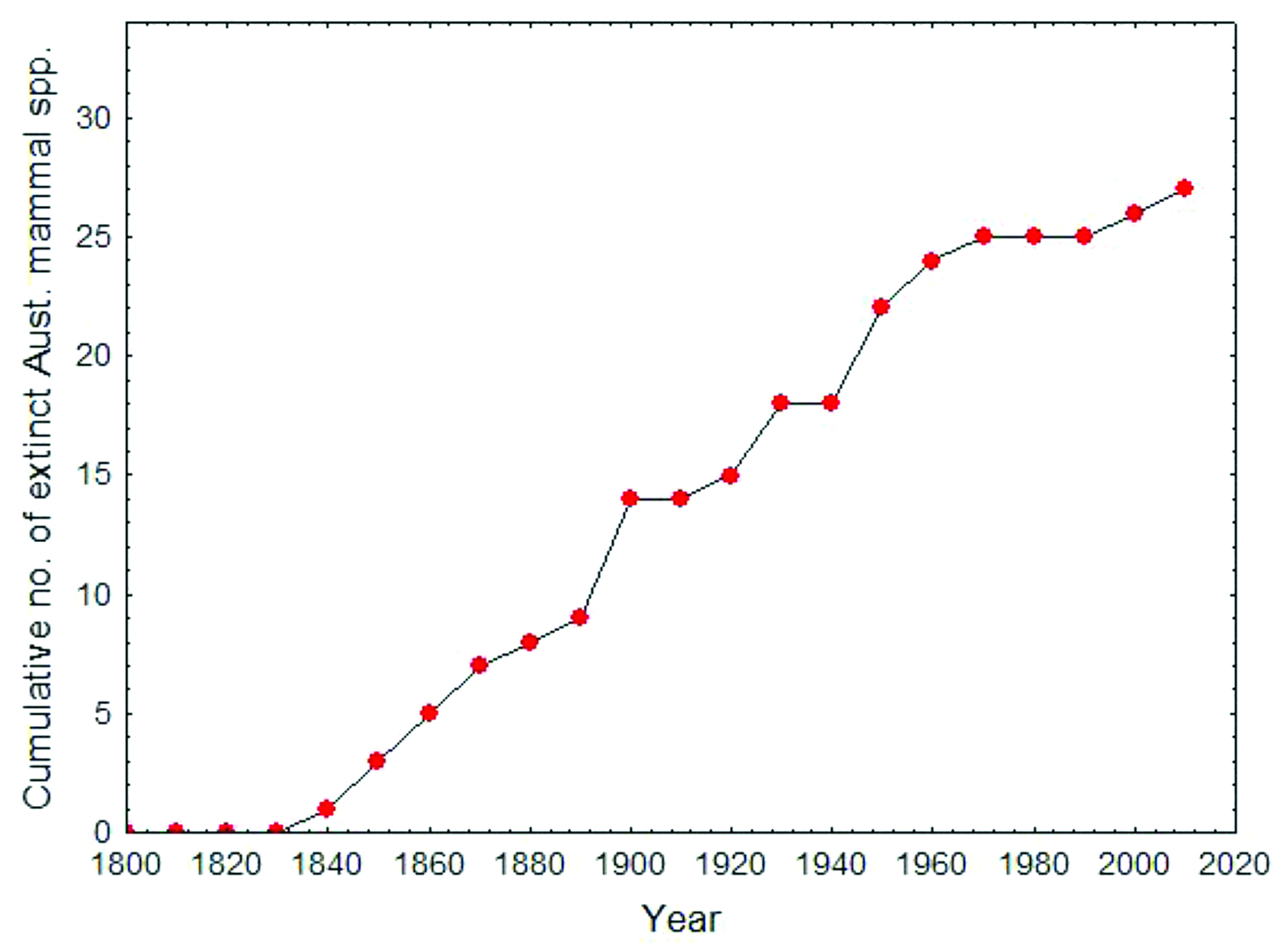

Figure 1. The cumulative number of extinctions of Australian endemic mammal species (excluding those extinct species for which the dating of extinction is too difficult to assess); modified from Woinarski et al. 2014).

Figure 1. The cumulative number of extinctions of Australian endemic mammal species (excluding those extinct species for which the dating of extinction is too difficult to assess); modified from Woinarski et al. 2014).

Buying time. It is surprisingly hard to find out what we spend on conservation of threatened species nationally, with budget papers providing little insight on direct spending.

However, our assessment indicates direct Commonwealth funding for threatened species recovery is about $41 million per annum.

Indirect but possibly relevant funding through programs such as Landcare amount to between $41–400 million per annum, though most of these programs do not target threatened species recovery. In contrast, the US Fish and Wildlife Service dispense between $AUD2.1 and 2.5 billion per year on

targeted threatened species recovery actions.

The US Endangered Species Act lists 175 fewer species than the EPBC Act, so they’re spending a lot more on a smaller problem. This reinforces findings by Waldron and colleagues in 2013 and 2017 that Australia is an egregious under-spender on threatened species relative to the size of our problem and the size of our economy.

So, what’s the good news here? The best news, reported by Waldron and colleagues, is that threatened species spending works: if you spend more, you lose fewer species. Go figure! Even better news is that the species that persist start to recover when the right amount of money is spent on them. The average change in listed bird populations in the US is a more than sevenfold population increase, compared with a decrease in non-listed birds (Suckling

et al. 2016). Because we spend so little on monitoring Australian threatened species, it is hard for us to derive comparable figures, but early results from the TSR Hub Threatened Bird Index indicate substantially negative trends for Australia’s threatened birds as a whole.

So, what’s the difference? For a start, the US Endangered Species Act mandates spending on recovery, while our Act doesn’t. The fate of our threatened species would much more likely match the US’s positive trends if we were to increase funding by approximately tenfold. As context, that would cost the overall budget less than the current exemption from diesel fuel excise for mining companies.

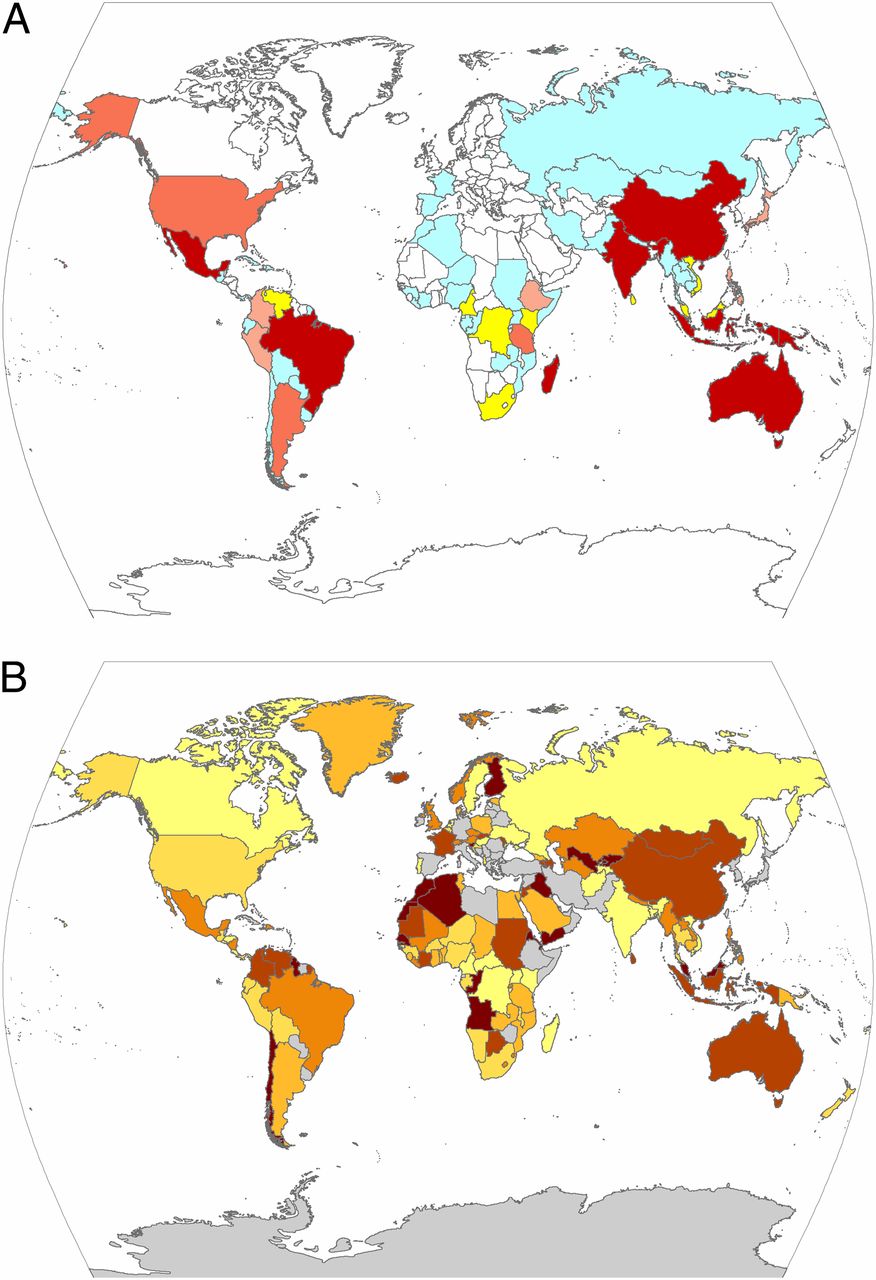

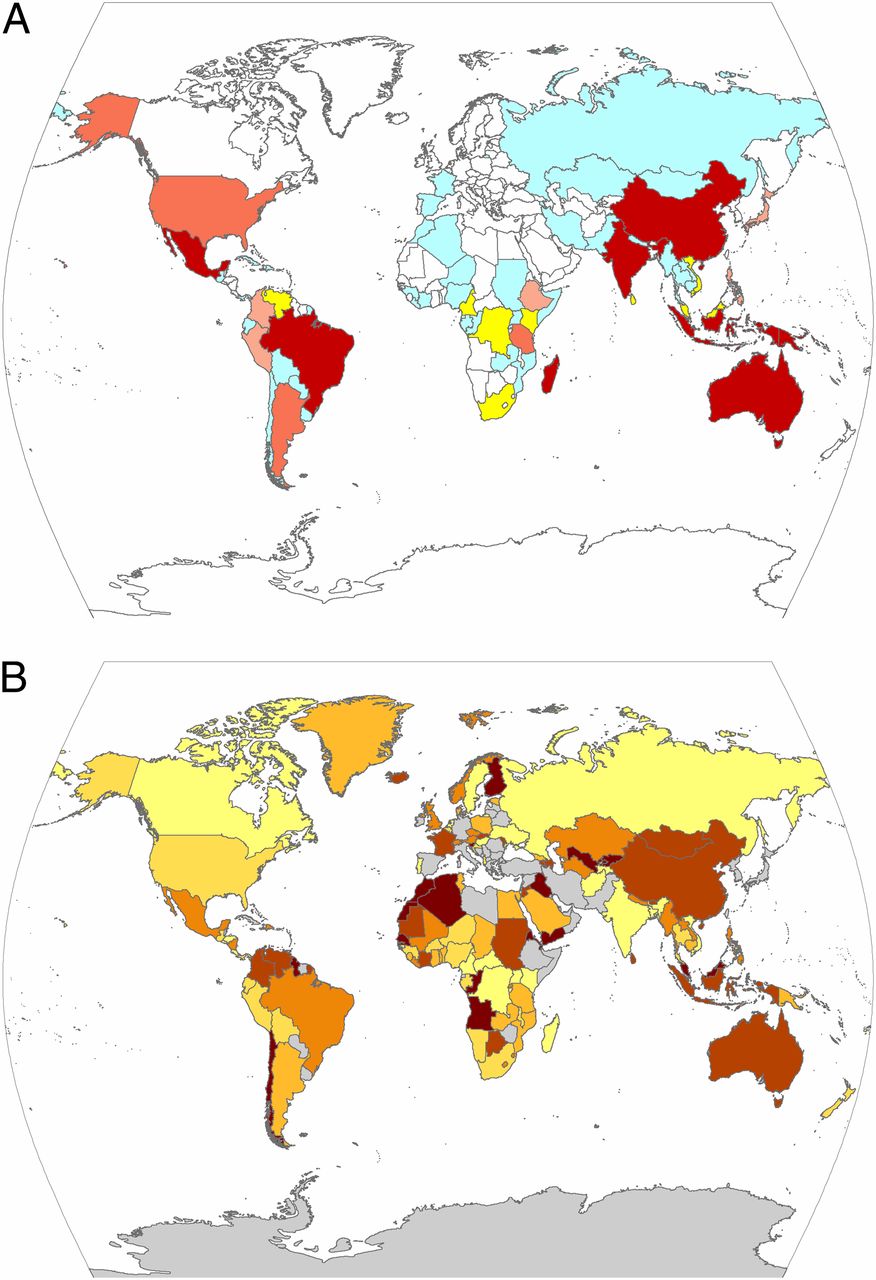

Figure 2. (A) Levels of threatened global biodiversity stewarded by each country. Colour coding: white and blue showing very low and low levels of threatened diversity; yellow, medium diversity; and the four red colours, high levels of threatened diversity, darker reds indicating higher values. (B) Underfunding levels - darker colours indicate worse underfunding. (Waldron

Figure 2. (A) Levels of threatened global biodiversity stewarded by each country. Colour coding: white and blue showing very low and low levels of threatened diversity; yellow, medium diversity; and the four red colours, high levels of threatened diversity, darker reds indicating higher values. (B) Underfunding levels - darker colours indicate worse underfunding. (Waldron et al.

2013)

Who’s counting? Hardly anybody, as it turns out … Our submission reviewed the current state of threatened species monitoring in Australia, highlighting the need for significantly more monitoring effort. This reiterated some key messages from our recent book

Monitoring Threatened Species and Ecological Communities:

- One in four threatened species are not monitored at all.

- Where monitoring does occur, its quality is generally poor.

- In the extreme case, species could slide to extinction without us knowing.

- We have no national overview of trends in Australia’s threatened species.

These come recommended. Our submission wouldn’t be a true TSR Hub production if it failed to make specific, tangible and policy-ready recommendations to help slow the

rate of species loss. Here are just a couple:

- the establishment of more regular reviews of the conservation status of listed species

- provision for emergency listing under the EPBC Act

- adequately resourcing threatened species recovery action in line with funding levels shown to result in recovery in the US

- committing to, and adequately funding, effective monitoring, public reporting and interpretation of trends in individual threatened species

- bolstering regulation of activities that lead to habitat loss and degradation

- providing stronger incentives for private land holders to improve habitat retention and restoration on their land.

The Hub is committed to helping governments at all levels achieve these outcomes.

Here, I have outlined just three of 11 sections of our submission. Other components include the adequacy of laws for protecting threatened species, the role of Indigenous people, and the ecological impacts of species loss.

The ability of the Hub to pull together authoritative and comprehensive submissions highlights the benefit of having a national threatened species research hub. It affirms that the Hub comprises people who are utterly dedicated to recovery of threatened species, not just threatened species research. The desire to leave a legacy of real-world impact defines our Hub. It requires us to be ready and willing to provide frank and authoritative advice when asked, and sometimes when we’re not.

The recovery of Australian threatened species has long presented a formidable challenge for governments. The information provided in our submission, and that of many others, offers a pathway for governments to review, reflect and improve on current policy and practice. From this evidence, we hope that this Senate Inquiry takes this rare chance to significantly improve the fate and future of Australia’s biodiversity.

Professor Brendan Wintle

Director, TSR Hub -

b.wintle@unimelb.edu.au References Legge, S., Lindenmayer, D., Robinson, N., Scheele. B., Southwell, D., and Wintle, B. (2018). Monitoring Threatened Species and Ecological Communities. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

Suckling, K., Mehrhoff, L. A., Beam, R., & Hartl, B. (2016).

A wild success: A systematic review of bird recovery under the endangered species act. Center for Biological Diversity. Available at:

https://www.esasuccess.org/pdfs/WildSuccess.pdf.

Waldron, A., Miller, D. C., Redding, D., Mooers, A., Kuhn, T. S., Nibbelink, N., ... & Gittleman, J. L. (2017). Reductions in global biodiversity loss predicted from conservation spending. Nature, 551(7680), 364.

Waldron, A., Mooers, A. O., Miller, D. C., Nibbelink, N., Redding, D., Kuhn, T. S., ... & Gittleman, J. L. (2013). Targeting global conservation funding to limit immediate biodiversity declines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(29), 12144–12148.

Woinarski, J. C. Z., Burbidge, A. A., and Harrison, P. L. (2014) The action plan for Australian mammals 2012. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

Top image: Green and golden bell frog. Photo Adam Parsons

Figure 1. The cumulative number of extinctions of Australian endemic mammal species (excluding those extinct species for which the dating of extinction is too difficult to assess); modified from Woinarski et al. 2014).

Figure 1. The cumulative number of extinctions of Australian endemic mammal species (excluding those extinct species for which the dating of extinction is too difficult to assess); modified from Woinarski et al. 2014).