Could toxoplasmosis have a role in mammal declines?

Monday, 16 March 2020Toxoplasmosis was introduced to Australia by cats, who continue to spread the disease. It is known that the disease affects Australian mammals, and that many Australian mammals are suffering dramatic declines. It was completely unknown, however, whether these declines are linked with toxoplasmosis. Dr Nelika Hughes from The University of Melbourne gives us the scoop on her team’s investigation of Toxoplasma gondii prevalence across Australia and whether it has played a role in mammal declines.

Loss of habitat and changes in fire regimes are often put forward as contributors to Australia’s appalling mammal extinction rate. The role of introduced herbivores and carnivores has also received widespread attention. But several researchers have noted that significant historical declines occurred in some areas well before the establishment of rabbits and foxes.

Similarly, the recent and sudden decline in mammal species across northern Australia does not correspond with obvious changes in the usual suspects of fire, habitat loss or introduced species. In these – and other – instances of mammal decline, however, novel diseases introduced to Australia following European settlement might have played a role.

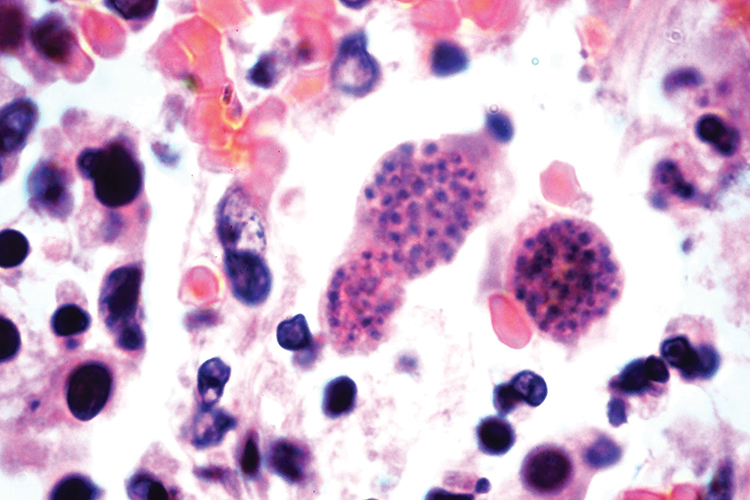

A strong candidate in this regard is toxoplasmosis. Caused by the ubiquitous protozoan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, the disease was introduced to Australia with cats (the parasite’s definitive host), but also needs to infect a different mammal or a bird (an intermediate host) to complete its life cycle.

When a cat is first infected it sheds infectious Toxoplasma oocysts in its faeces, contaminating the environment with approximately 2–5 million oocysts over a period of 1–2 weeks. This oocyst stage is important as it is the only time when the parasite is exposed to the environment.

Intermediate hosts become infected by consuming these oocysts while foraging or grazing, although transmission can also occur through the consumption of infected animals.

The effects on infected mammals and birds are twofold. The initial infection can make animals very sick, potentially leading to sudden death. But animals that survive this period also face challenges, including skewed sex ratios, reduced risk aversion and an attraction to cat odours, possibly increasing the risk that the infected animal will encounter a cat.

Toxoplasmosis was introduced to Australia by cats, who continue to spread the disease. Image: Public Domain CCO

A role in mammal declines?

Cats are found across Australia, and Toxoplasma infects a wide range of native species. To learn whether Toxoplasma is playing a role in Australia’s mammal declines we mapped the prevalence of Toxoplasma in feral cats across Australia, looked for any environmental factors associated with this distribution, and then extrapolated the likely exposure of native mammals to Toxoplasma.

To estimate the level of exposure that native mammals have to Toxoplasma we combined information on the density of feral cats across Australia (estimated by another hub project), with new knowledge on cat infection rates across the country that was estimated by this project.

We estimated cat infection rates by analysing feral cat tissue samples from 25 locations across the country. Feral cat control programs provided a ready supply of tissue samples in which to screen for the parasite, and we then used quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) to screen these samples for Toxoplasma. Published data on Toxoplasma prevalence in feral cats from an additional 22 locations gave us a combined dataset of 1001 cats from 47 sites.

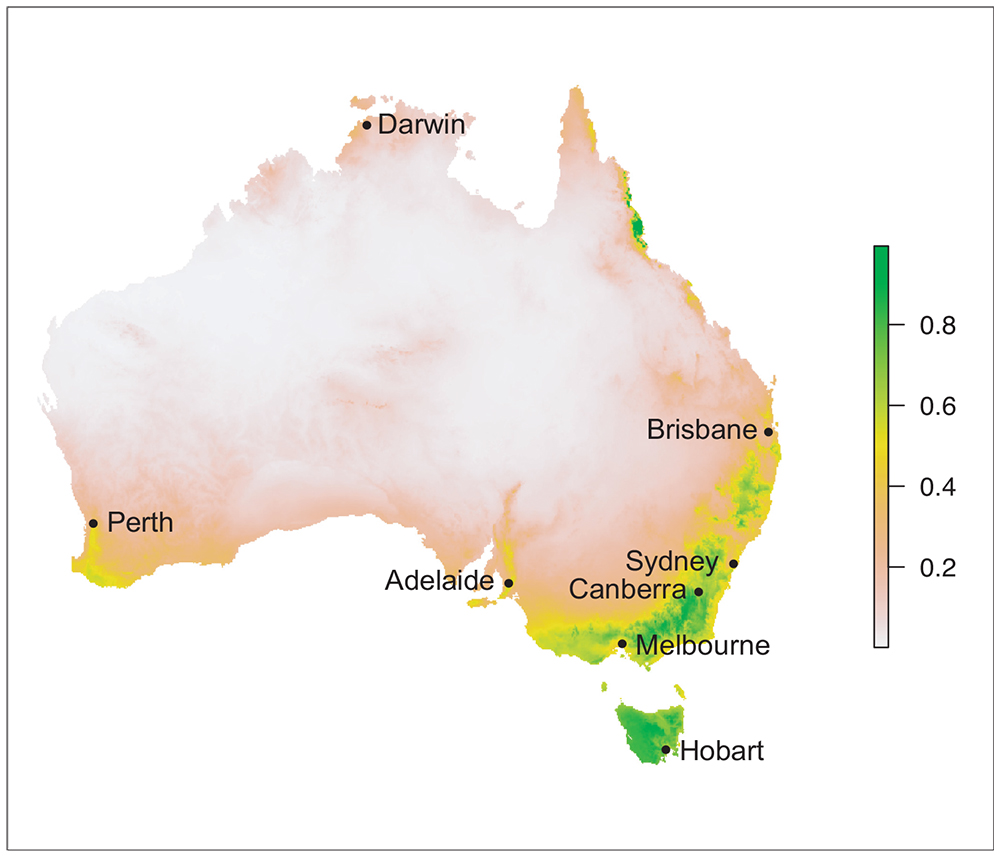

Next we built a model of Toxoplasma prevalence based on the infection data combined with data on temperature and rainfall across the country, as temperature and moisture are known to affect Toxoplasma oocyst survival. As conditions can be very different in urban areas compared to surrounding bush and rural areas in terms of cat density and environmental conditions, we also included urban areas in the model.

What we found

Approximately 40% of our sampled feral cats were infected with Toxoplasma, but we found that Toxoplasma prevalence in cats is highly variable across Australia. The main predictors of prevalence are temperature, rainfall and urbanisation and, in urban areas, cat density is also influential.

Toxoplasma prevalence decreases with increasing temperature and increases with increasing rainfall. Increasing rainfall also mitigates the effect of increased temperature, so Toxoplasma oocysts can survive in warmer areas, to some extent, as long as there is enough moisture.

North and centre too hot and dry

Toxoplasma appears to be either absent or at very low levels across large parts of central and northern Australia. While there is no shortage of cats in these regions, the environmental conditions appear unfavourable to the survival of the oocyst stage of the parasite. The finding of low prevalence in these regions argues strongly against Toxoplasma playing a major role in mammal declines — both recent and historical — in these areas.

High rates in cool and damp areas

Our results also show very high prevalence of the parasite in the cooler and damper parts of the country, particularly around the Great Dividing Range, and in Tasmania. Here, Toxoplasma may well have a substantial, under appreciated, impact on native mammal populations.

The model predicts high prevalence of Toxoplasma in feral cats in Tasmania, along the eastern coast of Australia south of Brisbane, and along the southern coast of Victoria.

Urban reservoirs

Urban areas have high Toxoplasma prevalence rates. In urban areas temperature has a stronger effect on prevalence rates than rainfall, possibly because in urban areas water is generally not limited.

We also found that cat density becomes influential in urban areas, with increasing cat density resulting in increasing Toxoplasma rates. This finding has implications for human health, because controlling feral cats in urban areas may be a useful mechanism for reducing Toxoplasma risk to humans.

A worrying finding was that urban areas appear to act as reservoirs for Toxoplasma in otherwise unsuitable regions, giving rise to the possibility that this may allow the disease to adapt to the environmental conditions of these otherwise unsuitable regions. This could occur as urban areas will supply a steady stream of the Toxoplasma oocysts into surrounding areas (in cat faeces), the oocysts will be exposed to challenging environmental conditions on the edges of urban areas and, while most will perish, over time genetic variations may occur allowing some oocysts to survive until they are consumed by a secondary host. Natural selection will ensure that those best adapted survive to reproduce.

The threat of urban areas supporting adaptation of the parasite to hotter and drier conditions therefore provides an additional conservation-focused incentive to control feral animals in hot, dry urban areas.

Figure 1. The predicted prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in feral cats across Australia. The highest concentrations (green areas) are in the south-east and in urban centres.

A final word

While we did not directly examine infection prevalence in native wildlife, our results matched well with published data on Toxoplasma prevalence in native wildlife across Australia. While Toxoplasma looks to be exonerated from a role in mammal declines for central and northern Australia it may well be having a significant impact on Australia’s mammals in wetter and cooler areas. Urban feral cat populations may also lead to greater adaptation of the parasite.

This Threatened Species Recovery Hub research project was led by The University of Melbourne in collaboration with The University of Sydney and received support from the Northern Territory Government, Indigenous ranger groups and many other cat management groups across Australia. It was supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program. The research team included Nelika Hughes, Jack Dickson, Rebecca Traub, Jasmin Hufschmid, Danielle Stokeld and Ben Phillips.

For further information

Nelika Hughes - nelika.hughes@unimelb.edu.au

Top image: The Toxoplasma gondii parasite can cause severe illness and death in infected mammals. Image: Yale Rosen CC BY SA 2.0 Flickr