Measuring return on investment in threatened species recovery

Monday, 02 May 2016Whether it’s reducing hospital queues, improving social equity or recovering threatened species, taxpayers need to know their investment is producing results.

“We need to monitor threatened species so we can tell the Australian public whether we’re going forward or backward,” explains Project Leader and TSR Hub Director Professor Hugh Possingham.

“There’s a huge amount of data available about Australian threatened species but it needs to collated and analysed into something meaningful that will stand up to scientific scrutiny.”

“We need to report on the outcome of threatened species recovery actions like any other indices the country provides in areas where we invest, such as human health, social wealth and equity.”

“Although this is going to be difficult to establish, I’d compare it to measuring hospital queues for elective surgery. Taxpayers want evidence that their investment in the health system is reducing the length of those queues, or in this case, recovering threatened species.”

“There hasn’t been a lot of information from governments over the last twenty years to show the return on investment from environmental spending and we need to fix that. Sectors like health and transport are able to put forward their case with more compelling numerical evidence.”

Through Project 3.1 Hugh’s team will work with a number of partners at the state level and in the NGO sector - in particular, Australia’s states and territories, Parks Australia, individual scientists, Birdlife Australia, Bush Heritage Australia and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy to build a representative sample.

“Given the Federal government is investing a lot in threatened species recovery and we’re doing a lot of new science over the next five years - we’ll need to have a clear idea of what we’ve achieved and whether we’re actually recovering anything or not,” said Professor Possingham.

“This level of monitoring is similar to a company maintaining its bookkeeping - if companies don’t keep accounts they don’t know whether they’re making a profit or loss.”

The project won’t be limited to the threatened species the TSR Hub is focussing on.

“We’re looking beyond just the threatened species we’re researching and managers are taking recovery actions on, because that’s not a fair test. We need to get a picture of all of 1700+ animal and plant species at risk of extinction.”

“There might be one index for birds, one for mammals and one for plants. We might then be able to break it down to indices for regions (northern, arid and temperate Australia) and threats (i.e. land use change, feral predators, disease), so we could report on something as specific as ‘mammals affected by feral predators’.”

A prototype Bird Index may be delivered as soon as this year.

“Like any good research project – we don’t actually know if we can do it. But if we can’t get it to work for birds, we won’t be able to get it to work with anything.”

“From there it will be a fairly mechanical process of assembling as much data as we can and working with all our partners to analyse and communicate the indices.”

-

Threatened plant trends in the spotlight

Thursday, 11 March 2021 -

Australian threatened bird populations drop by half in 30 years on average

Tuesday, 27 November 2018 -

Call for threatened species data

Friday, 03 May 2019 -

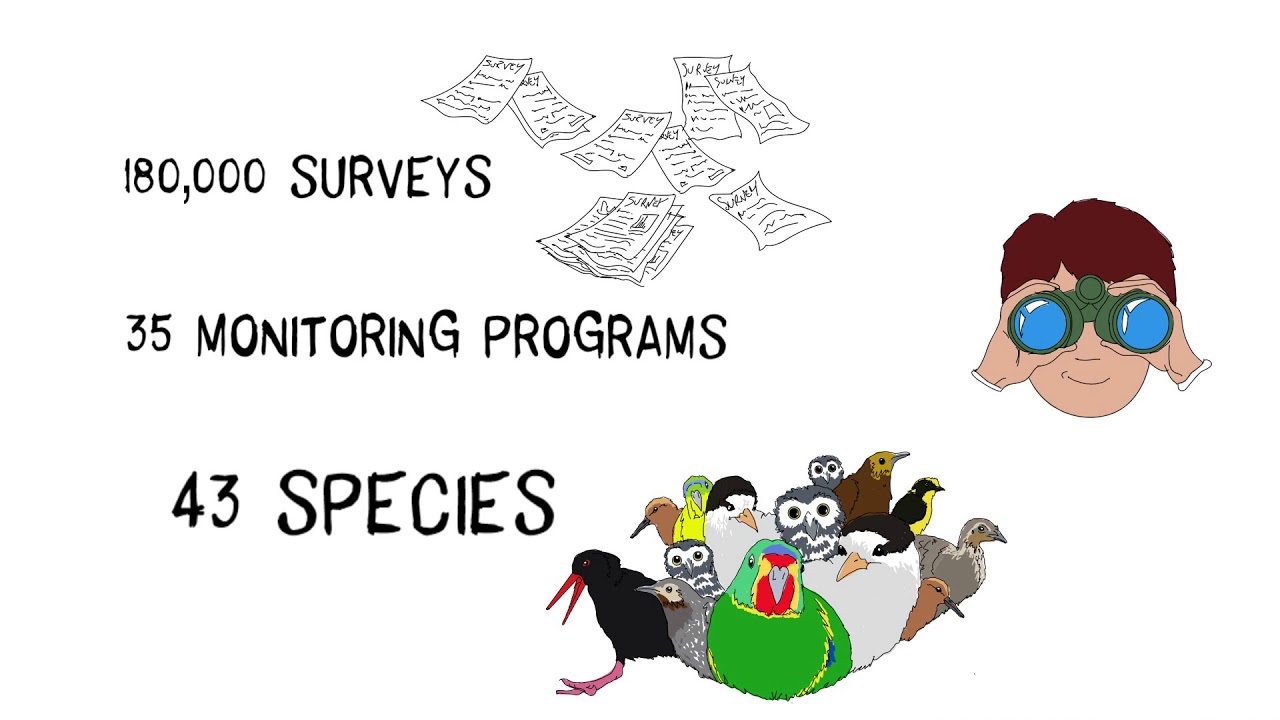

Calling for big data

Thursday, 06 October 2016 -

Trending now: The new Threatened Species Index for Australian birds

Tuesday, 12 March 2019 -

Planning under way for new index

Thursday, 09 June 2016 -

Threatened Plant Index of Australia: 2020 Results

Thursday, 03 December 2020